Publicité

Narcotics: How synthetics is reshaping the drug business in Mauritius…

Par

Partager cet article

Narcotics: How synthetics is reshaping the drug business in Mauritius…

The death of a policewoman on duty during an antinarcotics operation has thrown into sharp relief the fact that the authorities are struggling with the synthetic drug problem. How did synthetics rise in Mauritius and how is it changing the whole picture of drug business in Mauritius?

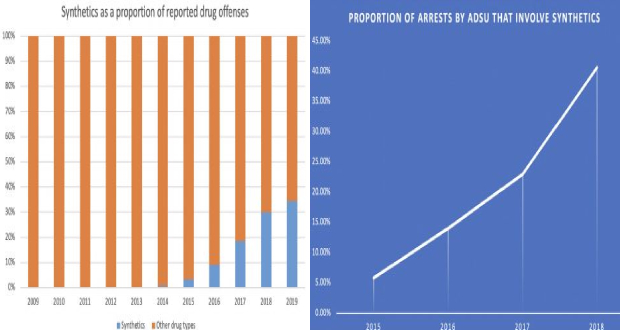

The death of woman police constable Dimple Raghoo during an anti-narcotics operation has only underscored the serious problem that Mauritius is facing when it comes to tackling the problem of synthetic drugs. And it is becoming a bigger problem; just this year, 15 people died from synthetic drug use. According to the latest National Drug Observatory Report (NDOR) released this month, no less than 41 percent of all drug-related arrests by the Anti-Drug Smuggling Unit (ADSU) involved synthetics, with the drugs accounting for nearly 35 percent of all drug cases reported to the authorities. A far cry from just a few years ago when synthetics was all but unknown in the country.

How is it that this drug has taken Mauritius by storm? Synthetics, as it were, was the product of good intentions. Researchers studying the endocannabinoid system, crucial for normal function, developed more potent artificial chemicals to replace THC (the active compound in marijuana) to better stimulate – and study – receptors in the brain. These studies were then hijacked by drug dealers to develop synthetic drugs, artificial cocktails to mimic and enhance the effect of marijuana. First appearing in the US, synthetics then spread to Europe before China became firmly established as a center for illicitly manufacturing synthetic drugs.

Sam Lauthan, former minister and one of the assessors who helped come up with the report of the 2018 drug commission, tells l’express, “A few years ago, when we were coming up with the report, it was estimated that there were as many as 400,000 underground labs in China; since then India too has emerged as a major manufacturer of synthetic drugs.” When the Americans and the Europeans realized they were facing a synthetic drug epidemic, the laws were tightened in these countries to fight it, beginning in 2003 in the US and 2008 in European Union states, leading the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to note in 2018, that synthetic drug manufacturers then turned to pumping these drugs into states where the laws to combat synthetic drugs were either weak or non-existent. The drugs commission report in 2018 called it ‘dumping’.

Mauritius first came to know it had a synthetic drug problem in 2013 with the authorities recording two cases involving synthetics. Just like synthetic drug cases in Europe, it started out with chemicals used to manufacture synthetics shipped via mail from China. The drug commission noted that no less than 95 percent of the chemical components to manufacture the drugs were coming from Chinese drug labs – and more recently from Indian labs too - and ordered online from Mauritius on underground sites on the dark web and the Silk Road.

Taken by surprise

The entrance of synthetics, the drug commission noted, had taken Mauritian authorities “by surprise”. These drugs were entering in various forms, Lauthan points out, “as powder, liquids, crystals and packaged as candles, fertilizers, bath salts, lipstick and even candy.” The drugs came in, dissolved in commercially available solvents, like benzene and acetone, and then sprayed on tealeaves and tobacco to be smoked. As synthetics started flooding in, the commission said, out of the 18 sniffer dogs kept by the police, not even one was trained to detect synthetics. Nor did the ADSU or the Forensic Science Lab have the proper equipment to break down the ingredients used to manufacture these synthetic drugs, nor did the Dangerous Drugs Act (DDA) list the chemicals used in manufacturing synthetic drugs as items of concern.

In 2013, the DDA was changed to include synthetic cannabinoids as an illegal drug, but even then, cases were arising where police were forced to let drug dealers go simply because their raids were taking place before the dealer had actually treated the (legal) chemical components into the (illegal) synthetic drugs. In 2019, the government significantly expanded the DDA to include such chemicals on its list. The Public Accounts Committee Report released in November last noted that government studies such as the Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance (IBBS) survey only dealt with the more traditional problem of injectable heroin rather than smoked synthetics, resulting in the authorities having no estimate of the actual number of drug users in the country.

When the authorities started cracking down on synthetics coming from abroad via the post office, that led to another problem. Synthetic dealers in Mauritius started cooking up their own cocktails in basements and garages to keep feeding the market. “This is when the danger really began as they started a trial-and-error process mixing different combinations of chemicals to make up for market demand,” explains Lauthan. In this, Mauritius synthetic dealers were simply aping European ecstasy peddlers, who dealt with a global shortage of methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) in 2005 by substituting it with different chemicals.

By 2014, ecstasy tablets in Europe were chemically unrecognizable. The result of this experimentation on the local synthetic drug market was a sharp spike in synthetic-related hospitalizations between 2015 and 2018. The number of hospitalizations following synthetic drug use doubled from 552 in 2015 to 1,089 in 2017, before starting to fall to 854 in 2018 and 834 in 2019. “This is because synthetic dealers in Mauritius were refining their product; after all, they didn’t want to kill off their customers,” Lauthan points out.

The shift

The nature of synthetics themselves is changing the Mauritian drug market. The first problem is that, since the manufacture of synthetics involves legal chemicals, it is hard to control these by law. “Solvents like benzene are available at any hardware shop or construction site,” says Imran Dhanoo, of the Idrice Goomany Centre for the prevention and treatment of alcoholism and drug addiction, one of the largest NGOs in Mauritius dealing with drug rehabilitation. Former Attorney General Yatin Varma says that this is becoming a real problem. “Synthetic drugs are easily produced and the DDA will have to be constantly updated to tackle it; it might not be able to foresee everything but it will have to constantly change to adapt according to the circumstances,” Varma insists.

Unlike plant-based drugs that Mauritius is used to dealing with, such as heroin or marijuana whose chemical components hardly change, synthetics pose a unique challenge. Within Mauritius alone, so far 35 varieties of synthetics have been discovered by the authorities. In Europe, the 2020 EU Drug Report found 50 new types of synthetics since 2019 alone, with the UNODC recording just under a thousand different combinations of synthetics worldwide thus far. What this means is that the DDA and anti-drug laws will have to constantly be playing catch-up as synthetic traffickers keep changing their product to stay ahead of the law. The drugs commission in 2018 also pointed to the challenge of convincing law enforcement to adapt to this style of combating drugs, pointing to officers shrugging that controlling the importing of legal chemicals (that could be used to manufacture synthetics) was not their job and the total absence of any kind of monitoring on the sale of such chemicals within the country.

The other factor is the low-price tag of synthetics. Unlike heroin or cannabis, which require land and time to grow, synthetics can be hurriedly cooked up in a lab and treated with a gram of synthetic powder to produce up to 300g of finished synthetic drugs. Lauthan gives an indication of this; a cannabis plant takes between four to nine months to grow depending on its variety, but a synthetic cannabinoid (the main form of synthetics consumed in Mauritius) just takes 12 hours to treat and prepare and it is ready for the market. “It’s so simple that even students are now doing it,” says Varma. Recently a 19-year old was arrested for preparing synthetics for sale. Because of that, synthetics are undercutting other drugs in Mauritius in terms of price: Rs100 for a dose of synthetic cannabinoids, compared to Rs300 for marijuana and Rs500 for heroin.

In many ways, the disruption on the drug market being caused by synthetics closely resembles the start of the heroin epidemic in 1983. A crackdown on cannabis (the traditional drug of choice) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, created a shortage and vacuum on the drug market that was swiftly filled by brown sugar (an adulterated form of heroin). “People simply switched to heroin, which was then selling for Rs12 to Rs15 a dose, and quickly addiction rates grew,” Dhanoo recalls. A transnational network quickly grew out of that with Mauritius, Madagascar and Reunion forming a smuggling axis for heroin, the rise of prominent drug barons. In 1985, following the publication of a report by Madun Dulloo, the idea of the death penalty for drug traffickers (an idea that still makes the rounds each time there is a major drug-related crime). Heroin soon found itself in Mauritian politics too, particularly following the Amsterdam Boys affair in 1985 when four parliamentarians were caught in Schipol airport, Amsterdam carrying 20kg of heroin. Subsequently, politicians accusing one another of being involved in heroin business became a regular part of Mauritian politics in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Ironically, the cause of the synthetic epidemic today is the same as the one, which caused the heroin one: the crackdown on marijuana. “What we are seeing at our centre is a generational shift in terms of drug use,” maintains Dhanoo, “about 60 percent of people come in to treat heroin addiction but now 40 percent are coming in to treat addiction to synthetics.” Dhanoo’s numbers closely mirror the proportions reported from addiction centres in public hospitals too, according to the latest NDOR. But with a twist: all those coming in after taking synthetics are aged under 24, whereas those coming in to treat heroin use tend to be older.

A new business model

For young people in Mauritius, cannabis is the drug of choice with police statistics reporting that most juveniles in Mauritius traditionally being hauled in for marijuana. But with the combined effect of a marijuana shortage on the market due to police crackdowns (150,503 marijuana plants uprooted by the authorities between 2017 and 2019), driving up the price of marijuana and the easy availability of low-cost synthetic cannabinoids, it explains why it is primarily the youth that are suffering from synthetics, so much so that by 2018, secondary schools were sounding the alarm. “Most young people – I have not come across a single user of synthetics over the age of 40 - coming into our centre say that they either cannot find cannabis on the market or it’s too expensive, which is why they switch to cheaper synthetics instead,” insists Dhanoo. This is borne out by police figures too: in 2018, the ADSU arrested 31 juveniles with synthetics; 20 with marijuana; and just 8 with heroin. In 2019, it was still 27 with synthetics and 11 with marijuana. The synthetic problem is basically a problem of the youth switching from marijuana to cheaper, and deadlier, synthetics. This was noted by the 2018 drugs commission report when it noted that, when it comes to marijuana, “repression has not really eliminated drug use; at best, it has moved the users on to other drugs, including new synthetics.” It is this insight, which has also led some parties, such as the Mouvement militant mauricien (MMM) to now call for decriminalization of medical marijuana and dropping prison sentences for marijuana possession.

A new kind of drug is also giving rise to a new kind of drug business. Heroin needs to be imported and is hence expensive. That created a new class of drug barons in Mauritius using drug mules from Madagascar and Southern Africa, and smuggling routes between Madagascar and Reunion, that has been roiling our politics and society for decades. Synthetics, not needing land or extensive smuggling networks, just an empty garage and some lab equipment to pump out cheap drugs, is giving rise to an entirely new business model with a new generation of younger – more low-key - drug traffickers. “From the discussions I have had with people coming in to my centre, it’s not the heroin traffickers that are branching into synthetics; this is new blood coming in, a new generation that does not need to operate in the same fashion,” concludes Dhanoo.

Source: Statistics Mauritius

Publicité

Les plus récents