Publicité

Economic forecast: rating Moody’s

Par

Partager cet article

Economic forecast: rating Moody’s

The Moody’s report on Mauritius, issued on 11 May, 2022, provides updated information on current and expected economic performance. Moody’s forecasts indicate an improvement in GDP growth, and a reduction in fiscal deficits and debt.

Mauritius has been rated with a negative outlook since April 20, with Moody’s stating that a downgrade was likely over the next 12-18 months. Which happened in March 21 with a lowered sovereign credit rating from Baa1 to Baa2, but not again since. Until Moody’s changes the negative outlook and affirms the Baa2 rating, the risk of downgrading remains. According to Moody’s, a fiscal consolidation agenda would allow for the negative outlook to return to stable.

However, there is a misguided attempt to interpret Moody’s projections as being favourable to Government’s economic policies, and to obviate the need for fiscal consolidation. This article seeks instead to strengthen support for an urgent review of fiscal and monetary policies, in line with the recent IMF mission statement, by taking a closer look at some of Moody’s economic forecasts.

Growth

Moody’s holds an optimistic view of tourism recovery in 2022, but highlights the need for more air travel flights. Moody’s foresees real GDP growth of 6.7% and 5.0% in 2022 and 2023. For comparison, the growth forecast of the IMF World Economic Outlook (WEO), April 2022, is lower at 6.1% for 2022, but higher at 5.6% for 2023, as shown in Table 1. Moody’s growth estimate of 4.8% in 2021 is outdated, and has been revised downwards by Statistics Mauritius to only 4%. The official growth projection of 7.5% for 2022 reflects more of wishful thinking than hard facts.

Fiscal Balance Moody’s forecasts of fiscal deficits are understated because they relate only to budgetary central government Focusing only on the budget deficit and ignoring special extrabudgetary funds does not provide a correct measure of the fiscal balance. Like the budget, special funds are used to meet all types of expenses, from subsidies to the wage assistance scheme to capital projects, but without the legislative and other reporting constraints. The 2021-22 budgeted expenditure for six major special funds was Rs26 bn, or 15% of total budget expenditure.

Unspent budget transfers to special funds are accumulated in one year to be spent in ensuing years, leading to surpluses followed by deficits in these special funds. A budget transfer to the Covid Project Development Fund of Rs15 bn in Sep 2020 was largely unspent. A further sum of Rs16.7 bn was transferred at the close of financial year 2020-21, raising the total balance of special funds in June 2021 to around Rs25 bn. Special funds showed a surplus of revenue over expenditure of over 5% of GDP in 2020- 21. However, a significant special funds deficit was budgeted for 2021-22. To derive a correct measure of the fiscal gap, the deficits of both the budget and of special funds should be added to obtain a consolidated deficit. As shown in Table 2, the consolidated deficit would be higher than the Moody’s budget deficit by 1.6% of GDP in 2021-22, and 1% of GDP in 2022-23, on account of the special funds.

It should be noted that the Moody’s deficit figure of 5.8% of GDP for 2020-21 is based on the treatment of the Bank of Mauritius (BoM) transfer of Rs60 bn, or 13.8% of GDP, as revenue instead of financing, contrary to IMF fiscal methodology. Despite the ludicrous claim of a balanced budget, the consolidated deficit in 2020-21, adjusted for BoM financing, stood at 14.2% of GDP.

Besides special funds, there are other reasons for revising the Moody’s fiscal deficit forecast upwards. The 2021-22 budget includes revenue of around Rs8 bn from withdrawals of income of quasi-corporations, namely FSC, CEB, STC, representing 1.6% of GDP. According to IMF fiscal guidelines, “funds withdrawn by liquidating large amounts of accumulated retained earnings or other reserves of the quasi-corporation are recorded as withdrawals from equity”, not revenue. Even allowing for part of the quasi-corporation reserves and other income to be considered as Govt revenue, the deficit for 2021-22 would be higher by another 1% of GDP.

The payment to Air Mauritius creditors of Rs12 bn, or 2.4% of GDP, should be considered as Govt expenses to bail out the airline, thus further widening the budget deficit in 2021-22. Surplus balances of special funds were initially used to finance the bail-out, refunded later by proceeds from an equity investment in Air Mauritius Holding by the Mauritius Investment Corporation (MIC), a special purpose vehicle of the BoM.

An equity investment in the National Property Fund of Rs2.4 bn, or 0.5% of GDP, should similarly be treated as expenses, reflecting a continuing bail-out of BAI insurance business. The true fiscal deficit in 2021-22 is close to 10% of GDP. Any expectations of effective fiscal consolidation are largely premature.

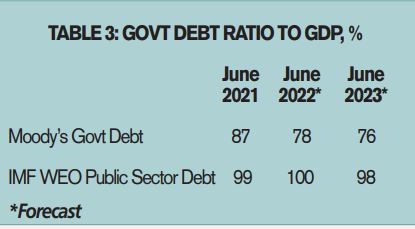

Government debt Moody’s debt analysis covers the debt of General govt, which includes (i) Budgetary Central Govt, (ii) Extrabudgetary units, and (iii) Local govt. It does not relate to public sector debt, as public enterprises are not included. Moody’s adopts the official figure of the debt ratio of around 87% of GDP in June 21, and forecasts the debt ratio to decline by about 9 points by June 22, and another 2 points by June 23, as shown in Table 3.

The official Govt debt ratio is artificially lowered by making a consolidation adjustment for the netting out of Govt debt held by special funds and other public bodies. Although Govt claims that this consolidation adjustment is in line with IMF fiscal standards, it is not considered in IMF and World Bank debt statistics on Mauritius. The IMF WEO’s public debt figure of 99% of GDP in June 2021 can be derived from Moody’s Govt debt figure of 87% by adding back a consolidation adjustment of 3% of GDP, and including the debt of public enterprises equivalent to 9% of GDP (87+3+9=99).

Moreover, an additional SDR allocation in Aug 2021 of about Rs8 bn, or 1.6% of GDP, has not been included in the latest Govt debt statistics, although previous SDR allocations are added to external debt. It is likely that the new SDR allocation is also not included in Moody’s debt forecasts. More importantly, the latest IMF WEO outlook expects a stabilization in the debt ratio, not a decrease as projected by Moody’s.

The MIC acquisition of equity in Air Mauritius Holdings for Rs25 bn, or 5% of GDP, did not only finance the airline bail-out of Rs12 bn, but also a Govt debt reduction of Rs13 bn. This exchange of equity in a state-owned company for central bank money is an example of quasi-fiscal financing, which the IMF has repeatedly urged Mauritius to avoid. Continued BoM money printing for Govt and the increase in nominal GDP contributed to reduce the debt ratio to 79% of GDP in March 2022, but also to a sharp worsening of inflationary pressures.

Conclusion

The deceptive accounting practices to obfuscate the interpretation of fiscal data will not distract Moody’s from evaluating the deterioration in the country’s fiscal situation. The IMF Article IV report on Mauritius will soon provide a detailed and independent assessment of fiscal and debt challenges.

As expressed in the latest Moody’s update, “a continued deterioration in debt metrics, beyond our current expectations, is among the main factors that would likely lead to a downgrade”. Moody’s draws special attention to the “very large financing of the 2021 budget deficit by the central bank, which increases the risks to the effectiveness of monetary policy”, adding that “weakening monetary policy effectiveness as demonstrated by rising inflationary risks would also likely result in a downgrade”.

An erroneous reading of Moody’s update should not divert the authorities from delivering on corrective fiscal action, and putting an end to the reckless reliance on central bank financing. The Mauritius Bankers Association recently stressed the need for fiscal consolidation to avert a Moody’s downgrade with spill overs that would severely damage banking and financial stability. The forthcoming budget exercise may prove to be our last chance.

Publicité

Les plus récents